Part Two: “There’s got to be a morning after”

As I mentioned earlier, contemporary critics were quick to read Allen’s films in terms of social criticism. As J. Hoberman notes in a passage worth quoting at length. “Disaster films were more often discussed as reflections of the economic crisis … or else as manifestations of Watergate—as if Watergate was not the most enthralling disaster film of all…

"the Disaster Film Cycle roughly coincides with the collapse of the Bretton Woods international financial system in 1971, the 1973 OPEC oil crisis, the 1973-75 recession, the 1975 collapse of South Vietnam—the very period which, according to historian Eric Hobsbawm, marked the end of the twentieth century’s post-World War II “golden age” and the reemergence of those social problems which, largely dormant for a generation, had previously characterized the critique of capitalism: ‘poverty, mass unemployment, squalor, instability.” 14"

One way the films dealt with such a laundry list of social ills was through ideological retrenchment. In many ways, these are deeply conservative movies. Most of them pit a single, heroic white male figure against forces of greed and stupidity, and maintain the importance of the traditional (pre Second Wave Feminism) family—or at least of the traditional heterosexual couple. All of them blame greedy individuals, more than the system itself, for failure. And in all of them, hope for a “morning after” rests with the future deeds of a few good men.

But there is emphasis on community, too. And as I suggested above, the way the films insist on the social significance of collective cooperation makes them far less reactionary than the Dirty Harry and vigilante cop cycle that ran at the same time. Even the depiction of women here is less invested in critiquing feminism than one might expect. Despite the films’ goal of reestablishing patriarchal power, there is a sense that the “new woman” might be a better partner for the “new” hero than a traditional woman would be. This is most clear in Airport (1970), in which it is the adulterous couple that is valorized in at least two cases. And in both these pairings (Burt Lancaster/Jean Seberg; Dean Martin/Jacqueline Bisset) the love that endures grows within, and is nurtured by, the workplace. While Airport hints strongly that the Martin/Bisset couple will settle down into a traditional family (she is pregnant and they are trying to decide what to do about that when the airplane bomber strikes), it posits the Lancaster/Seberg couple as a working pair. The film ends, as it begins, with the couple coping together with yet another airport crisis. Only this time, as the film makes clear, he’ll go to her place afterward for “breakfast.”

As noted above, these films are heavily invested the insistence on adhoc solutions and individual (as opposed to systematic) fault, there is also an implicit critique of the no-holds barred capitalism that results in the shoddy construction, dubious insurance arrangements, and unprincipled business decisions that cause catastrophe in these films. As J. Hoberman points out, “typically…[in these films] calamity arrives as a punishment for some manifestation of the boom-boom sixties” (Hoberman, 170). And here the films do mirror vigilante movies, as they insist that it is the competence and motivation of America’s managerial elite that must be questioned (Hoberman, 170). This is most directly stated at the end of Towering Inferno. When Susan Franklin (Faye Dunaway) asks architect Doug Roberts (Paul Newman) if a new building will be built on the inferno site, he answers “I don’t know. Maybe they oughta just leave it the way it is. Kinda shrine to all the bullshit in the world.”

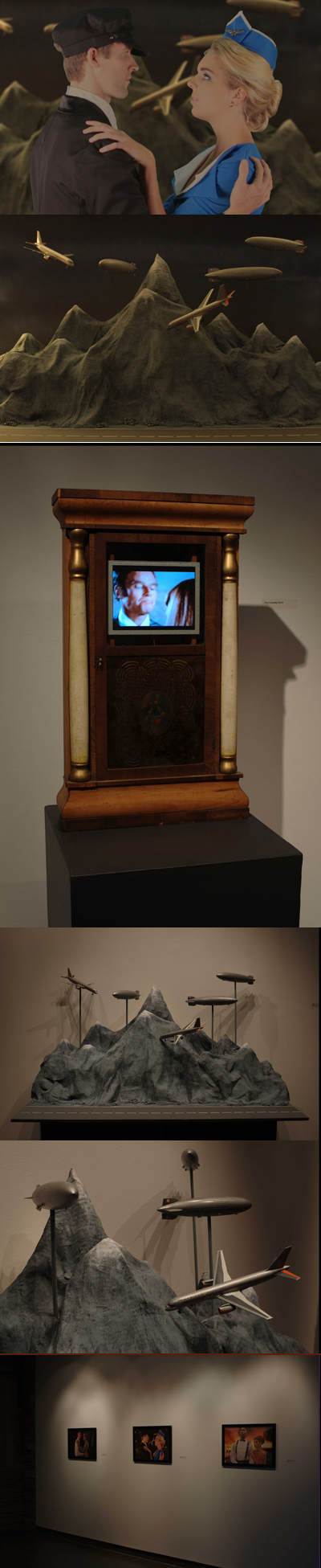

This is a strong statement. But hearing it now, post 9/11 and mid- extreme climate change, feels downright ominous. At this juncture, it would seem, Allen’s films can be read as a warning, as a final wake-up call to an America that was busily propping up the very kind of capitalism that figures—in these fictional worlds-- as the source of the problems they chronicle. Lowther plays with this prophetic, “portents of the real”15 feel through the use of imagery and backdrop. It’s not always clear in New World Disorder which catastrophe is being referenced. In a way, all disasters merge here; all disaster exists simultaneously on an endless loop. What distinguishes the disasters are not geographical referents or specific historic markers but, rather, the elements themselves: fire, water, earth, air.

As Lowther described it to me, the work began as a meditation on “the perverse pleasure of disaster/ruin,” and it references both “the way desire is represented in disaster films” and the “wish/desire for disaster” to come. At least initially, the author writes, he had an “optimistic view of disaster as a positive agent of needed change.” But in the course of working on this installation, he began to question that original assumption. Wondering if disaster were less “opportunity in crisis” than just “pretty damn ugly,” he began working through ideas of metaphor and punishment. I think it is a testament to the power of the installation that all these threads are present in the final work.

To some extent, this is always true in conceptual art. As Chris Kraus writes in her wonderful Where Art Belongs,“conceptual art offers viewers a journey along an associative chain.

"There is always a bottom. Or rather the work attains its own life by cannibalizing the half lives of its sources. Looping back through multiple tropes to arrive at its own existence, the conceptual art work offers itself the protagonist of an old- fashioned, well-crafted story composed through the collision of historical referents rather than characters. 16"

Only here, in addition to the collision of historical referents, we see a collision of elemental referents, the atavistic earth-air-fire-water chartings of an astrology which both explains the past and predicts the future.